Artist-Run KC: Digging Up Dirt with Davin Watne

Artist-Run KC: Digging Up Dirt with Davin Watne

Davin Watne, a painter based out of Kansas City, MO, and director of the UMKC Gallery of

Art, had a conversation with me regarding the history of Dirt Gallery and the role it played in

stimulating artist-run spaces in Kansas City. Dirt Gallery was located in the West Bottoms,

and rose to become a prominent and well-respected space in the arts’ community. Speaking

to me on behalf of this space, Watne mentions his personal goals, histories, co-leadership

and importance of the uprisings of these spaces.

Neal and Jessie. Image courtesy of the artist.

What was your motivation in starting Dirt Gallery? Who were the founders and what

motivated you to get involved?

At the time in the mid 90’s, there were not a lot of venues for emerging artists to exhibit in

KC, let alone the rest of the country. I think this “Alternative-Artist-Run Gallery movement”

started because artists just out of school wanted somewhere to exhibit their work. The only

galleries around town were showing big, blue chip artists from the coasts and the occasional

KCAI faculty member. There was very little in the way of local artists showing work here,

even though you had all this talent coming out KCAI. It was just assumed that if you were

serious about pursuing an art career, that you would move to a big city on the coasts or

Chicago. I found that I liked curating exhibitions when I was asked to help organize a show in

the painting department at KCAI while still in school. Then after school I wanted to keep

doing it. There was a great energy and excitement to the experience. At the time there were

a lot of cheap, big, wide-open spaces in the West Bottoms. Some recent grads from KCAI

had moved down there and had these great studios. They were very raw and open. They

would clean up the studios and exhibit their work, they called their space the Random

Ranch. As a young art student, it had a big effect on me.

Did the location of your gallery have any advantages or disadvantages?

Yes. The West Bottoms were very isolated and ignored, so you could do almost anything you

wanted and it would not bring the attention of the city’s authorities. This was a concern back

then because it was not zoned for living space and we were not supposed to be living there.

We could have parties, openings, musical events, film festivals. fashion shows all without

permits or a business license or anything. Everything was done on cheap with very little

money. We did have a few incidents with the police, but for the most part they left us alone.

The disadvantage was that it was hard to get people down there. This was before the

internet so, all invitations were done through the mail. People actually read the newspaper

listings then. The trains down there confused people, because they would block the street

and they were very loud. Our building was very raw, dirty and had no insulation, so it would

get blisteringly hot in the summer and freezing in the winter. We would develop all kinds of

clever ways to stay warm or to cool off.

Exterior view. Image courtesy of the artist.

Did your personal beliefs ever conflict with how you ran the space, such as showing a

specific artist or their work about more sensitive subjects?

Not so much, as I think we were pretty democratic about exhibitions. We tried to maintain a

facade of professionalism. We had artists send us proposals and we would do studio visits.

We always had each other to bounce ideas around.

How did Dirt Gallery come to be and who was involved in its founding?

In the beginning, it was Jeremy McConnell who found the space. Back in school, he was

producing a magazine called Flavorpak and he was looking for a space to have parties in to

raise funding to print the issues. I was looking for a space to start a gallery, so we teamed

up. It was too much to rent for just us so we would sublet the other rooms to our friends and

fellow artists. It became a hang out for lots of people and a bit of a revolving door of

roommates and hanger-ons. It was a bit of a flop house. We were always trying to make rent

so we needed people to pitch in. Our standards for renting the space were very flexible. After

the first year, a new core group of artists moved in that consisted of Leo Esquivel, Max Key,

and Neal Wilson. The four of us really tried to make a consistent effort to raise the standards

of our exhibitions and the gallery profile. Leo Esquivel became the most crucial in assisting

with gallery functions and future programming. He and I really became the face of the

organization.

How long was the space in operation?

About seven years.

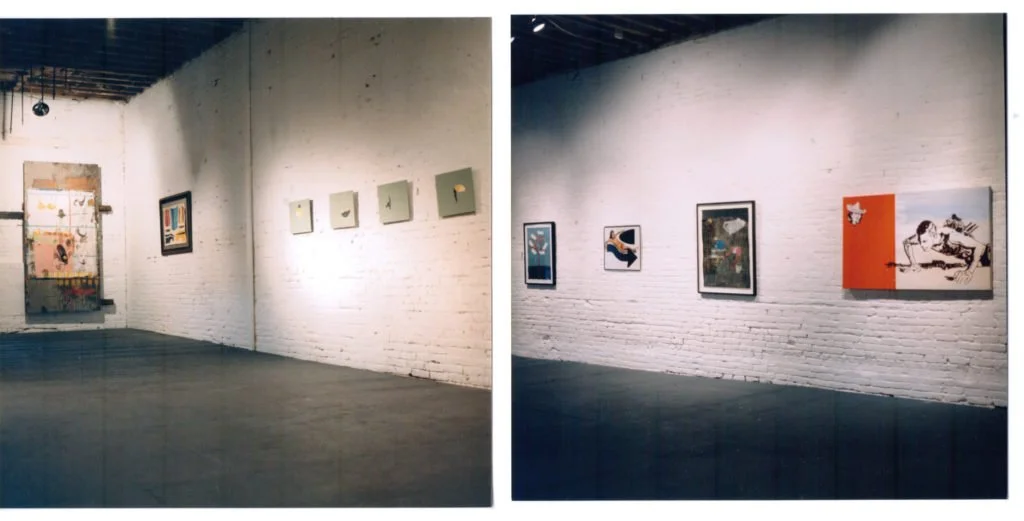

Image courtesy of the artist.

What was the most memorable show you had at Dirt Gallery?

That’s a difficult question, and I think everyone you talk to about back then will have a

different show which they remember better than others. There were two shows that stood out

for me. The first one was called “Pre-Millennium Stress.” It was the first time we began to

think on a national scale.

This was before the internet, so people would mail out invitations. We started getting these

invitations from artist run, alternative spaces all around the country and it began to dawn on

us that this is a real movement and people were trying to connect with each other. So each

of us contacted friends who lived in other cities like Boston, Houston, New York, Chicago and

asked them to send us work. The result was a very interesting snapshot of what young and

emerging artists were creating at the time. The other exhibition was a show of a Japanese

artist curated by our friend Ryuta Nakajima. They came from all over Japan and some even

came over from Europe to be in this show. A few of them had never met each other before,

and came to the Dirt Gallery on complete faith in what Ryuta had planned. Their English was

not very good, but they stayed with us and we had a great time, cooking big dinners and

playing music. I saw such inventive ideas, amazing craft and intense dedication to their work.

The result was really impressive, hence why it’s one of my favorite shows by far.

What effect did Dirt Gallery have on your studio practice?

Well, it was taxing on my practice. Even though we had amazingly large studios, we were

very busy with the gallery.

What were your expectations in participating in this project?

Truthfully, I had little expectations. It always felt like we were going to be kicked out for

violating city ordinances or not have enough for rent, but I was happy with what we had

created. People had such a strong connection to the place. Students would come to

openings as freshmen and then possibly show there once they graduated. We were the first

place to exhibit a lot of well known KC artists, like Peregrine Honig, Jamie Warren, Seth

Johnson, David Ford, Nathan Fox, etc. There are too many to name.

What was your most memorable show?

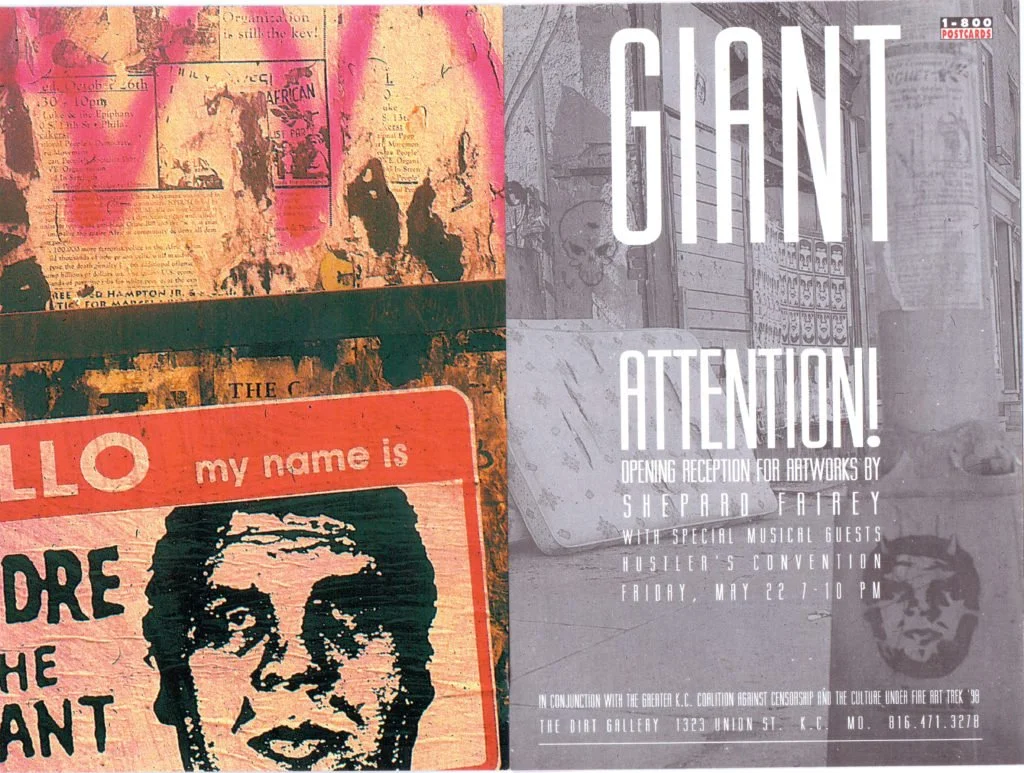

Shepard Fairey.

Shephard Fairey exhibition flyer. Image courtesy of the artist.

Why did the space close and what were its challenges?

We got burned out. I got married and tired of living in a dirty old building. I think we all need a

change. At that point, there were so many of these spaces in KC. It really spiked by the time

we closed. I think the advent of Charlotte Street Foundation changed the landscape by

offering a lot of opportunities to young artists from a real institutional standpoint. This took

the DIY motivation out of the next generation of recent grads. The internet changed things a

lot as well. Communities just moved online, so things started to change.

Does creating artist-run spaces spike your interest? Would you think about

participating/founding another one in the future?

No, I am very focused on my work at the moment. Also, I am the director of the UMKC

Gallery of Art.

What do you think the importance of spaces like this are in an arts community such as

Kansas City’s?

I think they play an important role. I think about organizations like Plug Projects, or Fifty Fifty

and I can see the same spirit. Although, these spaces are so damn organized and better

funded. Today, I don’t think we will see anything like we did in the 90’s, since there is just less

of a demand for those spaces. Kansas City has changed, there are more institutionally

backed venues and opportunities now. I do see more of this in other cities like Baltimore. But,

I guess anything can happen. Never say never.

Can you talk a little about what you do now?

I teach studio art at UMKC and curate and manage the University gallery. This gives me an

outlet to curate shows and help emerging and mid-career artist have access to a venue in

which they can experiment.

If you had advice to give to someone who wanted to start an artist-ran space, what

would it be?

Buy property and think more about a retail component. Foster young collectors.

Artist Run KC is a print publication from Informality that encapsulates a partial history of

artist-run spaces in Kansas City.

Artist-Run KC features interviews with former Charlotte Street Foundation Artist Award

Fellows who have managed spaces or contributed in a meaningful way to Kansas City’s

artist-run scene. This zine was produced by Informality in collaboration with PLUG Projects

and commissioned by the Charlotte Street Foundation for their 20th anniversary celebration,

Every Street is Charlotte Street. Artist Run KC features interviews with David Ford, Tom

Gregg, Peregrine Honig, Mike Erikson, Madeline Gallucci, Erica Lynne Hanson, Garry

Noland, Glenn North, Dylan Mortimer, Sean Starowitz, Caleb Taylor, Heidi Van, Jaimie

Warren, and Davin Watne.

Artist Run KC launched at PLUG Projects on NOVEMBER 12th 2017 alongside their revised

PLUG book! If you are interested in a copy email editor@informalityblog.com