The Self and The World in Progress in dreamyou

dreamyou, an exhibition of paintings by Sophia Reed and Kyra Gross at Vulpes Bastille, was

a chaotic and surprising experience. I am enthused to see paintings by young artists of the

Midwest who are still compelled to investigate material and invest in the future of painting

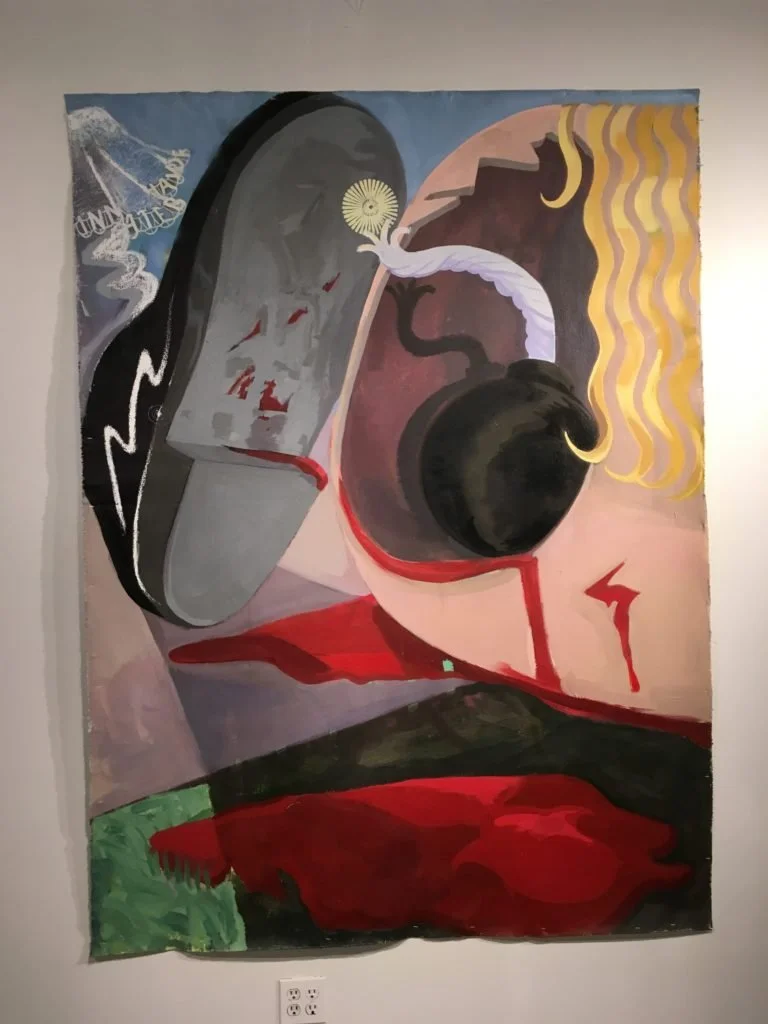

after reports of its death. Most of Gross’ paintings are big, particularly one entitled What’s

Inside, with a gaping hole of a head, a foot coming down hard, and a lit bomb in the wide

tunnel barreling through a mind, leaving a flat pool of blood. There were some brightly

bizarre portraits by Reed, some recognizable as historic and others adopting a kind of

painting interested in describing non-humans—farther from reality. These portraits,

sometimes very direct in their nature, like Mona In Space (which looks as it sounds, the

Mona Lisa shrouded by a psychedelic, cosmic environment), conflict those that reference a

more distorted figure. The neon and airbrush throughout are characteristics creating

synonymity between Gross’s and Reed’s work, visually. Posturing some dreaminess, there

was also a pressing sense of doom. This led me to think these paintings in particular aim to

announce the death of some tradition, perhaps toxic to their own system of becoming.

Sometimes affecting a larger majority, it’s a way to cope. Digging into the many motifs

present, and the knowledge I had of the two artists, I staged this interview to pose some

questions.

Julia Monte: As figure painters, both attending the same college (University of Central

Missouri) with a similar coming of age story within the community of the christian church—

where the idea of a “big man in the sky” (to quote Gross) watching over impacted a lot of

your decisions—what connections were you drawing between your works that led you to

curate an exhibition in our attempt to view ourselves? Where do you find indicators of this

attempt in each other’s work?

You, Mona in Space, and King and Queen, by Sophia Reed. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Sophia Reed: Kyra’s work is narrative and powerful. I’ve always been interested in the ways

she tells stories through painting. We are both interested in the rewriting of history in a way.

These works are reflections of self and the world we witness. The location and culture we

have been raised within is extremely similar. The work showcases the unique ways each of

us has processed this similar culture. dreamyou highlighted the thread of desire and reality

we both face daily in a world without known meaning. With our materials we attempt to

comment on, or maybe change the space which we navigate.

Kyra Gross: Sophia and I were texting and I used the term “color slut” to describe how we

interpret and use pigment—it made both of us laugh because it really does describe us as

painters. We’re both interested in people as individual selves, as characters in a scene—

curious about context, histories, and how we manifest ourselves. We’re both very

form/human oriented, which we both struggle with. Portraiture seems trite at this point,

especially when using ancient materials, but it still mystifies both of us. I saw that Sophia was

trying to expand her visual parameters and the ways she was beginning to translate her

ideas about portraiture and defining the self. I appreciate Sophia breaking the flatness of

painting because I am so stuck in the rectangle.

Strange Flower by Kyra Gross. Photo courtesy of the artist.

JM: The scope of art history and the church are underlying ideas in your works respectively.

It seems like both art history and God are ways in which we, as a collective, can see

ourselves, that goes beyond the visual perceptions of who we are. You both handle

portraiture so differently, but it’s apparent that the idea is being stretched across the works in

dreamyou. How does portraiture tie into the ideas of interpreting identities for each of you?

SR: Portraits can outlast our lives on Earth—this blows my mind. These artifacts go on to tell

about the age in which we lived. The ways we see the past have been molded by the ways

history has been recorded. Verbal communication is lost, unless written and cared for.

Certain facts are elevated because of their use. The church is part of a larger cultural

movement that took over, wars were waged and civilizations saw themselves from

constructed truths. Both God and Art are seen through their recorded histories. I was

reimagining a history that gave us a limited view of the real world. How would these artifacts

look if they included personal moments like clipping your nails, and what happened to the

history of the less fiscally enabled?

I hope these images flip the coin of portraitures’ past. I hope they are inclusive and

welcoming to their viewers. For so long only the wealthy were painted through commissions

but here the subjects are sporting basketball jerseys and brushing their teeth.

Woman Artifact II and Lord Toothbrush by Sophia Reed. Photos courtesy of the artist.

KG: I grew up with the venerated human form—in painting, I remember orange fingers in an Alice

Neel’s work, in photo I remember Mapplethorpe’s naked men, and in church I remember the

symmetry of Jesus on the cross. The historical significance of portraiture has changed and no one

is paying you to depict them front and center in holy, even light, besides landed gentry. In my work

for dreamyou, the figure is never center and either zoomed in (What’s Inside), running away

(Guston’s Granddaughter), jammed in, or leaving a trace of themselves (Strange Flower).

Portraiture reveals a truth about the portraitist and the portrayed that I continue to find

troublesome yet fascinating—that each of us is an individual oriented towards our own

methods and unconscious ideals. I know that’s so simple, but it really does shock me daily. I like

how the history of portraiture is getting thicker and longer.

JM: There is more than just paint at play here, but it is a dominant factor of both of your work.

How do you each see painting as a part of a mechanism for talking about systemic

problems?

SR: I am interested in taking paint, something with a terribly long history, and interacting with it.

Paint allows for simple and complex expressions through color and symbols. Some of these

symbols are invented and others are stolen. In several of the pieces I will take a frame from an

older painting that has been elevated by an institution and insert a new subject. In You, I

replaced the Virgin Mary with a more familiar subject to me. Mary is portrayed countless times in

paintings because of a religious dominance. If we keep elevating the same kind of work, we start

to normalize a certain way of living.

For a long time men were the only painters, the wealthy were the subjects and these are the

artifacts we are left with to see the past. Using paint to swap and reimagine subjects creates

a new way of seeing the problems of the past.

Top: Jammed Printer by Kyra Gross. Bottom: Woman Artifact, Mona Artifact, and Woman Artifact II, by Sophia Reed. Photos courtesy of the artists.

KG: Painting is what I know how to do at this point—I would love to move beyond it. I went to

a school (UCM) where there was a lot of respect for liquid pigment and what it could do; one

of the few “world building” mediums I can think of. Using color to create a space – it’s an old

magic trick. As for making formally hung paintings, it seems more acceptable then standing

on a corner with a sign—it’s a way to signal to others who are also living under similar

systems. I use paint to show others what systems have defined and continue to determine

myself and my path.

JM: There are a lot of indications of narratives in each of your work—Sophia, you are

investigating many materials that call for different executions which has paved paths for

different narratives as well. Kyra, the similar uses of paint and mark in your work at a

relatively similar scale has led me to interpret your work more like one narrative, spliced up.

Are larger narratives the main factors that challenge your work or determine the subjects of

your paintings? Do you ever find that the larger narrative presents an overwhelming amount

of ways to deal with constructing accessible images?

SR: I like looking backward and forward, at myself and the world around me. It’s not always

easy to constantly be looking in and beyond the now. There are endless narratives to talk

about but I try not to let it overwhelm me because I really do enjoy making. My work is the

one place I feel like my voice is strengthened. I get to talk about the things that are bothering

me or that fear I have. Zero is a good example of that overwhelming feeling. The subject is

framed by a zero, the symbol I’ve worn around that’s on an old t-shirt I have. They gaze over

a large fence only to be blinded by the sun. This painting was a look into my own struggles

with the day to day, the weight in living and my unending want for something more.

KG: I don’t weave too complicated of a cosmology with narrative work, it gets inaccessible after a

certain point. I was thinking about this when I made Guston’s Granddaughter—I keep a painter

family tree, which I add to every so often, which helps ground me in the history of art and identify

painters whose ‘families’ I am a part of. The larger narrative to me is bigger then just my work, and

connects me to other artists dealing with the weight of individual consciousness, the absurdity of

the role of artist, anxiety about time, and the acceptance of advancing tech as commonplace—

maybe it will have a name once historians look back at art production during this time.

The exhibition presented ideas of the unfinished, and the impending doom that comes with our

relationship to projects started, and those that have fallen away. There is the blank frame

surrounding Lord Toothbrush and loose marks from an airbrush or paint brush; there is an space

untouched by the marks, very present elsewhere on the canvas, on the computer screen in Kyra’s

Jammed Printer. In some areas of the works and across the gallery, I could see there was an

expanse present, like many points of the narrative left unfinished—left for the viewers to fill in.

The state of the work was hard to determine at times, but I feel like the “unfinished” is an idea

worth staying away from, even if unintentionally, to address ideas expressing more certainly the

importance of changing systematic structures. Although, changing these structures remains

unfinished business. While the sense of incompleteness was present, it existed at the boundaries,

between the space and the painting, or the viewer’s identity and that of the painting;

contemplating the flux of boundaries around our existence, wherever those exist.

What’s Inside by Kyra Gross. Photo courtesy of the artist.

I thought about the painting again, What’s Inside, the one gaping hole in the head and the

impending explosion and squashing of a foot that were reinforced by the broad, cavernous

attitude of the gallery. The painting had the power to make those on adjacent walls seem

much smaller—not sure if to their demise. Despite my perception of the difficulties in curating

in this large gallery, I thought about how the setting of the work deeply influences its context.

In this space of becoming, were constantly confronted with the idea that we are still in

progress, but by creating intentional contexts through our conversations and collaborations,

we can find footing in this unstable postmodern ground. The dichotomy of depicting the form

that is either aiming more towards realism or dramatized depictions of characters—a key

idea all around— shows some characters in adversity with their surroundings, yet they are

planted there, firm, rooted, and feeling through it.