Woman’s Work: A Conversation with Misty Gamble on Decade

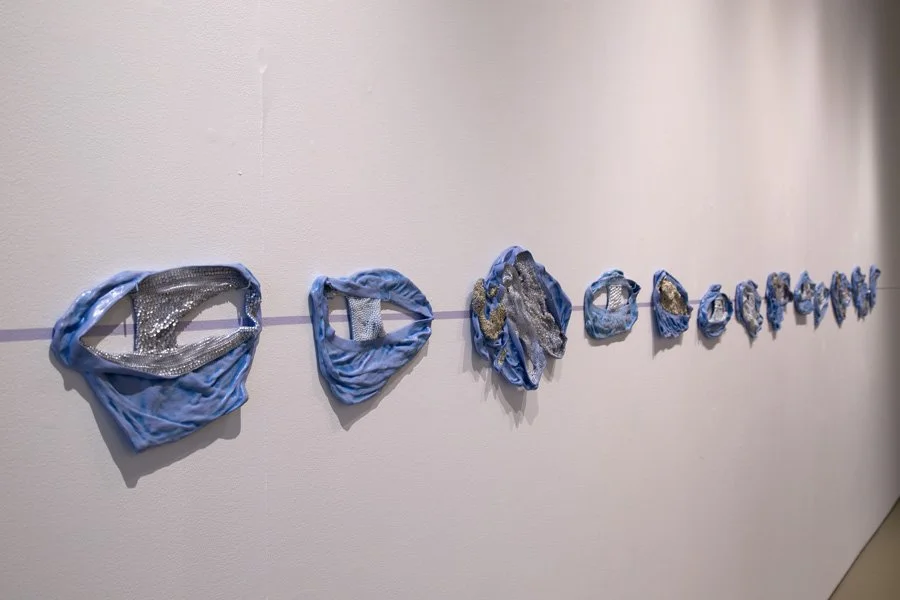

Blue Sunday by Misty Gamble. Ceramic, pearls, rhinestones, beads. Image courtesy of the artist.

The invitation to peer inside women’s underwear is hard to resist. Strewn across the gallery

wall, the ceramic artist Misty Gamble’s confrontational “Blue Sunday” stimulates a reaction of

curiosity and repulsion. Shaped like they were just removed and left crumpled on the floor,

the ceramic panties expose a strip of fabric rarely glimpsed in a public setting, sparkling and

colorful with costume rhinestones pasted to the private interior. The installation suggests a

body, and the inner functions of a body, without introducing the figure herself. A simultaneous

desire to approach and avoid means “Blue Sunday” successfully interfaces with our own

sexual desire, since we are not looking at newly shed intimates, but baked clay in disguise

as lingerie. We find ourselves in the physical Uncanny Valley where the subjects of

“Decade,” ten years of Misty Gamble’s agitated feminine expressions, become real enough

to raise questions.

Our meeting at YJ’s offers an interestingly contextual view of bright white BRIDE text in the

window across the street, a falsely angelic glow advertising wifehood like a sought-after

brand in the dark evening. It’s an appropriate backdrop for a conversation with an artist who

spent her life thinking about desire, traditions, and what it means to be female. Across the

small table, Gamble recounts the creation of her huge wall installation, “Forevermore.” “This

was finished in 2016, but it took a year and a half and a lot of hands to make. ‘Forevermore’

is only a fraction of what we actually produced in the studio,” she lays her hand on the image

of the lilac ceramic wedding cakes between snaking gold ribbons, installed vertically on the

Leedy-Voulkos main gallery wall. “I did these in the symbolic colors of bridesmaids: lavender and

white. I criticize conventional ideas of what makes people happy, such as being a bride, having

glamorous weddings, the notion that more is always better.”

Forevermore by Misty Gamble. Ceramic,

flocking, Ralph Lauren gold metalic paint. Photo

credit: E.G. Schempf

More is better in the case of the installation. Almost every piece in the show employs the use of

multiples to overwhelm an idea and drive the viewer to consider what limits we will go to to have

excessive wealth and status. At a distance, “Forevermore” becomes an illusion of wallpaper that

has sprung up out of the second dimension. The gold material woven between the lilac cakes

outlines an unmissable vulvar shape, locking in the inseparable bond between societal decadence

and primal desire. Ceramic wedding cakes direct the conversation to a ravenous hunger for social

authority, and one of the means of acquiring it. Excessively adorned hairdos and desserts exude a

passion for wealth, status, and sexual parading. Figures are grotesque and out of proportion, but

still decked out in facsimiles of the finer things. Gamble’s unflinching criticism is rooted in her

formative years. Rather than damn outright the norms of wealthy Palm Beach and Los

Angeles trophy wives, Gamble adopts the role of cultural anthropologist to observe the ways

consumerism and lifestyle are inextricably linked by status, which changes color and shape

in each location. Palm Beach is garish and bright. LA is fashionable and severe. “I used the

Kardashians for some of my research to find out what women of a certain status want from

the world. But it’s odd to be commenting on it, and to come from it, make work about it,

satirize it, and want to sell it,” she considers. “I always knew I would make the work I wanted

to make, and nobody was going to stop me, because the only thing I want to be is authentic.”

Authenticity itself is under the cultural microscope of Gamble’s studio. The disheveled piles

of pastel pumps borrow imagery from every women’s department store in the nation. The

artist’s name in a Kate Spade-esque font inscribed on the inner arch denotes factoryprocessed

shoes at an affordable price. As style consumers, we too can wear cheap and

reasonable heels out into the world, provided we don’t mind them coming apart after their

factory set sturdiness has worn off. Lucky for us, fashion is easy to replace.

Tan Hands by Misty Gamble. Ceramic, resin. Photo credit: Dan Wayne

The same fascination with the lifestyle of the rich and vapid amplify “Tan Hands,” a series of

nineteen hands sticking out of the wall, showcasing gaudy faux diamond rings, in a manner a

woman with such a rock might exhibit to her friends. Prim and dainty, fingers stiff and angled

down to give the admirer a better look at the towering stone atop a gold band, “Tan Hands”

explores the culture of pride that comes with following convention. But even with a rotation of

studio assistants through the years, Gamble cast her own hands for the piece, uncovering

another layer of personal history in the procession of wives-to-be. “I’ve been one of them,”

she says, flexing her retired piano hands. “I’ve come from these worlds, but I was always the

outsider.” As an outside observer, Gamble’s comments could be misconstrued into bitchiness

if one neglects to consider the intellectual analysis the artist subjects herself and her topics

to. None of us are really outside the reach of pretty things, of being liked by our peers. “Tan

Hands,” like other work in the show, examines a type of solution to our cultural insecurities in

a personal manner.

Betsy After School by Misty Gamble. Ceramic. Image courtesy of the artist.

Misty Gamble grew up in Los Angeles, where the lines between culture, class, and kitsch are

more blurred than in the Midwest. While she was pursuing her MFA in San Francisco, she

earned the reputation as a troublemaker in the male dominated ceramic program. “I did

different things to antagonize my professors. I set out to make work that was so beautiful and

terrible in its horrendousness, that it couldn’t be avoided. Women are told throughout their

lives: be pretty, be smart, get educated. But for god’s sake don’t make any waves.” The

figures in “Decade” evoke a visual puppetry without the strings, but the gesture of her

subhuman figures recall the unsettling weightlessness that animates a marionette.

Metaphorical strings attached to each woman and woman-like caricature are socially

imposed by the greedy clamoring of society to have more, to prove more with frivolity. “Sweet

Terror” came out of this drive to challenge what society expected of women and women

artists. The childlike figures in “Sweet Terror” are at once humorous and terrifying, like

demonic waifs escaped from a personified version of daily insecurities. The green teen on

roller skates, “Betsy After School,” reacts to her environment by messily eating dessert in the

middle of the floor, one hand stuffed underneath the folds of her pleated skirt. All the figures

in “Sweet Terror” linger somewhere between real and imagined, on the cusp of becoming

human, but denied by their desires and the imposing expectations of the environment they

were born into.

Gamble’s ten year retrospective is presented at the perfect time, and every piece in the show

is worth seeing. Today, femininity is continuing to be redefined by strength and courage, and

the bold figurative work in “Decade” is a reprieve from the enigmatic conceptualism that

dominates a male-driven scene. “People are so scared and fearful, and that’s the last thing

we should be right now. I’m going to keep making this work because I won’t be bullied,”

Gamble says of recent political events and the timeliness of the show. I nod in agreement,

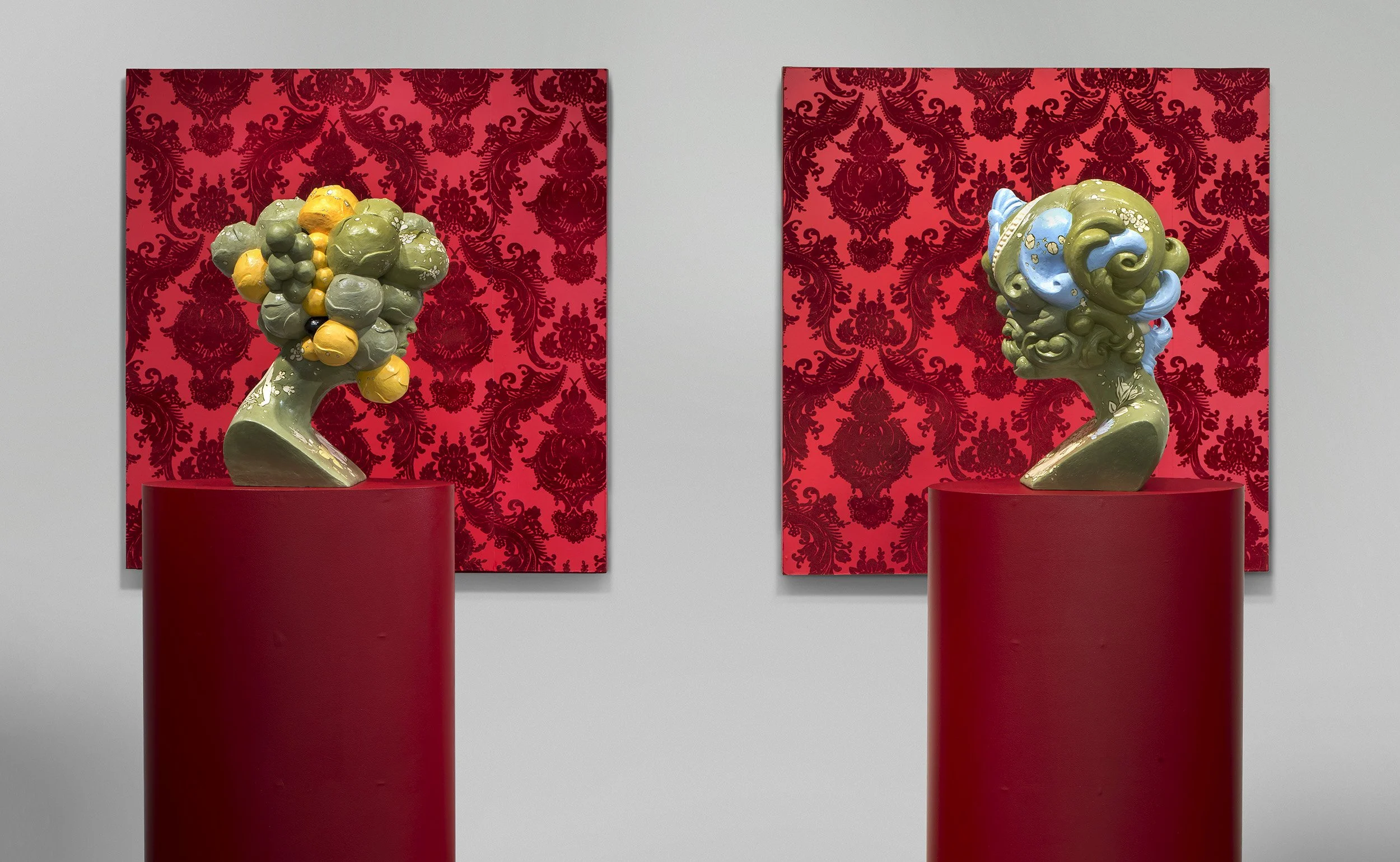

recalling the stoic busts “Decadence” and “Luxuriant,” two perfectly styled figures whose hair

denies each a chance to speak or listen.

Misty Gamble “Decade: Selected works from 2006-2016” is on view through April 1st at

Leedy-Voulkos Main Gallery (2012 Baltimore Ave, KCMO Hours: Thurs-Sat 11-5)