An Embodied Encounter With queer abstraction

It is difficult to make value judgments on works of queer abstraction; in fact, it is antithetical to do so. Instead, I offer an entanglement of sensory observations and visual/textual relationalities for readers to dis- and re-entangle as they see fit.

queer abstraction is a national touring group exhibition currently at the Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art in Overland Park, Kansas. This iteration features twenty LGBTQ artists and sprawls throughout the museum, occupying multiple spaces.

Image courtesy of the museum.

Posted on the walls of the exhibition are quotes from art historian David J. Getsy’s manifesto, “10 Theses on Queer Abstraction.” He stresses that both ‘queer’ and ‘abstract’ are fluid terms that, by nature, resist definitions that pin them down and overdetermine their meaning.

Even though the point of ‘queer abstraction’ is arguably to get comfortable with indeterminacy, multiplicity, and open encounter, rough definitions of ‘queer’ and ‘abstraction’ function here. Thus, my embodied experience engaging with the work in the show responds to these considerations.

Queer is a divisive term–some consider it derogatory, but many have reclaimed it as an umbrella term for the LGBTQ community. Queer can be a noun–one can be ‘a queer’–but it is not just an identity politic, it is also a mode of being. A rejection of stable identity categories and all forms of essentialism is central to understanding queerness, embracing fluidity, multiplicity, and relativism. Queerness aligns with the peripheral. Everything is queer in some way or another!

Image courtesy of the museum.

In abstract art, formal relationships within the artwork can allegorize social relationships. Getsy points that while a dominant curatorial strategy is focused on rendering recognizable queer bodies and spaces, abstraction is a visual tactic that allows queer subjects to represent themselves as they see fit. Not only is it a form of self-expression, but it is politically resourceful when rendering oneself visible can lead to violence in an anti-queer society. Perhaps you can tuck these frameworks in the back of your mind while engaging with queer abstraction; the best way to appreciate the artwork in the show is to experience it openly.

The first work that captivated me was a print called Rainbow Room by Edie Fake, an artist known for their comic-zines. Art deco motifs serpentined their way across the surface of the work, which became difficult and architectural, conjuring images in my mind of MC Escher’s Relativity. It was all pastel and illusionary, Op Art, except for a rocky texture in the corner that provides an organic, earth-toned grounding again.

Hung opposite the Fake works are the textile designs of Paolo Arau. The medium continues a long art historical conversation on how textiles were once relegated to the margins of the art world. Curation of this medium is far too exciting and innovative that to merely use terms as ‘craft’ or ‘domestic art’ undermines its historical importance. Made up of geometrical patterns, the imprecise lines of these works act as aporias, queering the perfect painterly grids that have long been associated with the ‘abstract.’ One could label them ‘queer’ because they subvert what we expect: rather than appearing machinic and disembodied, Arau’s textile grids are soft, bright, and squishy. Lines are not entirely straight, and points don’t exactly match up due to the stitched cloth surface.

Occupying another wall of the first gallery space are prints by Matthew Garcia. Superposition of Us is one print in particular that caught my eye. I immediately recognize the visual language he employs. (His prints also hang in the coffee shop I work at in the university town of Lawrence, Kansas.) They consist of entangled surfaces, impossibly woven together, edging toward illegibility, something unrecognizable and inarticulable. Showcasing an architecture of mind-bending planes, it looks like Dance by Matisse if the dancers were at a rave. You look at it, and you know somewhere Karen Barad is nodding in agreement.

Since we both live in Lawrence, I went ahead and had a short conversation with Garcia. Drawing a comparison to science fiction writers like Octavia Butler, he is “writing his condition through the work… that’s where it becomes political.” Seeking to “disrupt what people expect about abstraction,” his work aims to “render representational the abstract theories behind quantum physics.” Influenced by the relationships between queerness and quantum mechanics, since both have a fluid nature to them, he finds their intersection a place to create a speculative world. Describing his work as a gesture toward utopia, Garcia asks, “What would we look like if we existed as pure potentiality, away from gravity?” My conversation with the artist further complicated my notion of what an ‘abstract representation’ could be!

The juxtaposition of these three artists’ work, all occupying the same room, made me think about how queerness by nature is multiple: that is, different (perhaps even seemingly contradictory) forms of queerness can exist at once, in the same space. Something as precise, geometric, and horror vacui as Edie Fake’s print can easily be just as queer as Paulo Arau’s imprecise, organic, minimalist textile pieces. Garcia’s exploration of the relationship between queerness and particle physics echoes this conclusion: at the quantum level, common sense is replaced by complete indeterminacy..

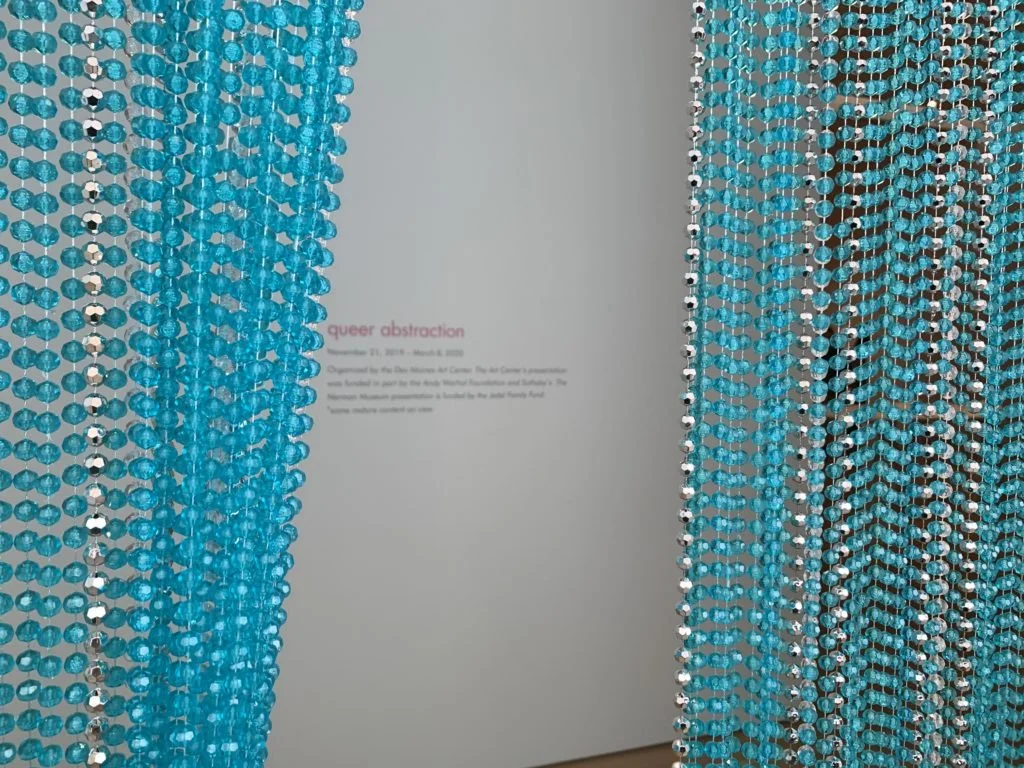

To experience the rest of the show in the second gallery, one must pass through a massive blue beaded curtain–this glimmering waterfall of plastic is Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ sculptural masterpiece, Untitled (Water). Designed a year before the artist died in 1996 to AIDS-related complications, he was known for his interactive conceptual sculptures. Gonzalez-Torres knew the parameters and execution of the piece would depend on the team that curates the show.

Here, the curtain made me think about the inside/outside distinction of the gallery space. Not quite in the main gallery, but not entirely outside it either, the sculpture acts more as a doorway than any kind of reliable, stable structure. Its positioning made me think about how LGBTQ people have had to erase elements of their identity to assimilate within institutional standards of normativity. Gonzalez-Torres’ work made inroads toward their accommodation in institutional structures while still gesturing toward what lies beyond their white walls. His oeuvre is primarily rooted in cultural activism and education, simplistic enough to be accessible. This curtain, installed differently in each exhibition venue, imparts an awareness of assimilation that demands the audience be a participant.

Walking through Untitled (Water), I felt like a molecule passing through a semipermeable cell membrane–a boundary as opposed to a barrier. And on the other side was my friend Hazel! Here is where we began our informal tour. The first thing I noticed was Sheila Pepe’s small, white, amorphous figurines. Occupying a sizeable white table accessible on all sides, the sculptures appeared child-like at first glance in their curious experimentation of form. Hazel explained to me that Pepe is primarily a textile artist. One figurine simply seemed to be a lump of clay that had been squeezed by a hand, but even such a simple creation quickly became something else in my mind, an apple core or a small votive.

After a few minutes had passed, I had to crack a joke. I astutely observed that everything in the room looked like dicks. However, it is essential to note that the artist rejects any phallic interpretation of the works–a sly dismissal of the trite trope of art critics claiming everything is a phallus, be it a sculpture, the camera, or the paintbrush. The coy joke plays out in Pepe’s sculpture, Hard and Soft Thing 2. Made up of a wall-mount with a stone on it, a long piece of soft fabric dangles suggestively off the wall. The curatorial strategy of the show enhances the meaning of the artworks displayed. The lighting shone on Hard and Soft Thing 2, for example, create shadows which suggest a pair of legs, further driving home the joke. Pepe’s figurines mimic the iconography of paintings behind them created by her wife, Carrie Moyer: droopy and organic, like a vase of fleshy flowers.

On the other side of the main gallery space, on the floor, lies Elijah Burgher’s New Horny Sun Vision. Viewers are once again invited to become participants in the artwork by walking on top of it. The extensive textile-like work bears repeating symbols of overlaid blue, green, and orange patterns that function as sigils. Sigils are markings with magical properties that activate to manifest. Each time someone participates by walking on the canvas (already a queer transgression of art norms, disorienting to the viewer’s expectations of looking at a painting on a wall), the physical interaction charges the sigil. It is a powerful articulation of how encountering artwork in everyday life can be a persuasive communication to change the lives of everyone involved.

Nearby hangs another textile–Moonflower, created by Bo Hubbard, a Kansas City-based artist. Designated by the label as an ‘artist rug,’ its surface is puffy, plush, and creamy.

Abstract biomorphic forms intermingle into what could be really anything–a desert quarry, a tufted topographical map, or clouds passing by in the dawn. Its position on the wall near the Burgher floor piece tactfully poses questions of functionality. It harkens back to my thoughts surrounding textiles and Arau’s ‘queering of the grid.’

Linda Besemer’s canvases deconstruct notions of art and its expected notions of presentation. They refuse the cage of the traditional frame, opting instead to be draped over rods as if they were bath towels. Instantly captivating, their intense geometric patterns and saturated neon hues remind me of the Mead notebook covers all the cool kids had in middle school. They have a commercial sheen compared to the massive, dark-toned works hanging just across from them, a reminder that there is always room for queer interplay between high art and low culture.

Image courtesy of the museum. Left: Nicholas Hlobo. Right: Harmony Hammond

Across from Besemer’s work is the work of Nicholas Hlobo. Hlobo’s work consists of four white canvases placed in a grid, stitched and stuck together by puckered black leather, adorned to loose ribbons. At first glance, it reminded me of baseball or some kind of Akiraesque body horror. After reading the label, which placed the work in the context of Apartheid (Hlobo is South African), I began to think more deeply about possible political readings, paying more attention to the formal interplay between white and black canvas and flesh, smooth and striated. In what way could these be allegorized to represent racial tensions, reparations, structural integrity? The work does not supply us with direct answers. However, it surely disorients viewers away from minimalism, homogeneity, business-as-usual. And, in doing this, it nudges them toward a deeper mode of aesthetic engagement that, if embodied in the day-to-day, would intrinsically operate to deconstruct normative concepts of race and the white supremacy they uphold.

The next room consists of three artworks, all by Prem Sahib. The largest of his works consists of a three-pronged arch. It resembles bathroom stalls, a nudge toward public cruising culture. The black tile that makes up the sculpture is reflective inside but not on the outside – only when you are passing through it are you visually reminded of yourself, your flesh. The ominous structure has an otherworldly presence

Another artwork in the room is a water fountain encased in a bluish resin. Initially installed in a gay bathhouse frequented by Sahib, he rescued this particular piece of plumbing when the place was shuttered and preserved it forever, materially and archivally, entombed in a sterile plastic, a frozen block of formaldehyde. What once occupied a zone of erotic pleasure, excitement, and engagement now sits in a museum. It is not allowed to be touched or used.

The process behind the work imbues it with a sense of sentimentality oft missing from artifacts designated in the archive as ‘queer.’ Perhaps cells of lip-skin or saliva were preserved along with the metal, giving it an equally abject and erotic quality.

Queerness will likely always remain an anathema. Rather than focusing on the intrinsic factors of the queer experience, abstraction provides a transcendent mode of expression that topically gestures toward what could be. In this way, queerness and abstraction go hand in hand–both are gestures toward some ideal realm. While the world might not be that place yet, queer abstraction is a thought experiment that asks, what if it was?