Building Equity Through Open Dialogue: A Response to What’s Missing in Kansas City

Image from Front/Space’s State of the Space event presentation courtesy of the gallery

Just a couple of weeks before 2016 came to a close, Front/Space hosted State of the Space,

an event which brought together an audience to serve as its “temporary board of directors.”

Madeline Gallucci and Kendell Harbin, who run the gallery together, started the night with a

presentation that shared the history and current standing of Front/Space. As an audience

member, I felt that the presentation was offered with refreshing transparency about how

exhibitions are selected, how the gallery’s budget is run, and why it is an LLC as opposed to

a nonprofit.

After the presentation and some questions from the audience, we moved on to an activity—

the co-directors asked us to take ten minutes and write responses to two prompts:

“Front/Space is…” and “When you think of the Kansas City creative community…What is

missing? What is already here?” After the ten minutes were up, I had just barely started my

third sentence and had not even begun to grapple with the second prompt. So, some weeks

later, this is my response:

—

Front/Space is a small, storefront, DIY, non-commercial gallery in the Crossroads Arts District

that invites artists to create experimental exhibitions and host programming. Front/Space is

physically small and awkwardly shaped enough that artists feel comfortable taking risks and

leaps in their practices. Within the Kansas City art world, there is an understanding that

Front/Space is a place for experimentation. Such experimentation sometimes yields

wonderful results, while other times it does not pan out.

This is perhaps the streamlined, nonspecific way to share the first question of what

Front/Space is. However, in conversations about Front/Space another descriptor that gets

brought up in attempt to define the space is exclusive—so much so that Front/Space’s

exclusiveness seems to be a hallmark trait of the gallery. Many people who I have come into

contact with feel as though Front/Space is there to serve a very specific slice of the Kansas

City art community. Again and again, I have tried to find justifications as to why Front/Space

might seem exclusive, but why it really is welcoming; making the problem just one of

perception.

Unfortunately, after leaving the conversation in mid-December, I felt disappointed in myself

for the false justifications I had put forward. For full disclosure, I have worked with, looked up

to, and share mutual friends with both of the co-directors. The Kansas City creative

community that we belong to is so small that it has given me the opportunity to forge many

close-knit relationships. But because of these relationships I am continually asking myself

whether this closeness prevents me from being critical. When does closeness turn the

community into a silo, making it difficult to open up to those trying to find their way in?

I want to push the conversation forward—to find out why I, and so many others, feel the

gallery is restricted to a certain set of social groups when I don’t believe that reflects the

intention of Front/Space.

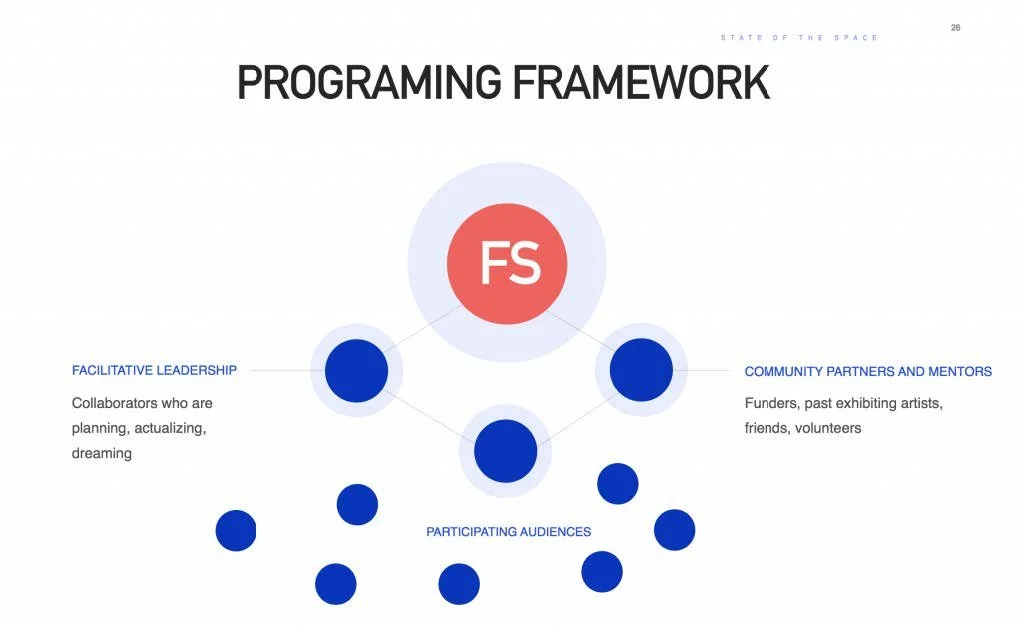

Image from Front/Space’s State of the Space event presentation courtesy of the gallery

When asked the reason for turning curatorial decision making to artists who have previously

had exhibitions at Front/Space, Harbin alluded to the co-directors wanting to avoid showing a

limited selection of artists. Gallucci and Harbin don’t want to only give shows to artists who

look like them, think like them, and are their friends. However, with an audience that was

majority white, full of Kansas City Art Institute alumni, many of whom are in the same social

circles, the State of the Space was an immediate reminder that working towards a less

insular community is very much a work-in-progress. For me, one of the most urgent answers

to their second prompt—what is missing from Kansas City’s creative community?—is that we

need to make more progress toward racial equity in order to create less exclusive and elitist

social dynamics.

I am particularly interested in race and ethnicity because it is an access point to understand

privilege and so many of the social dynamics underlying our art world. When we talk about

race and ethnicity, we have to consider economic class, access to education, inaccessible

language built into that education, and the limits of our social reach. The arts do not function

separately from the rest of the inequity in this country, so we need to keep our eyes open to

how, not if, the art world mimics the systematic racism that surrounds us.

A huge part of me believes that these gaps need to be primarily addressed by spaces and

organizations that are structured around the experiences of marginalized groups, and are led

by the members of those groups. While such organizations and spaces already exist, I look

forward to the day when more emerge and when the Kansas City community is challenged

on every front to recognize the incompleteness of our cultural awareness. But that does not

mean that white-run spaces can continue to ignore the critical part they play in addressing

similar questions.

To understand this inequity, I think turning to the local higher education system can often

provide a starting point. It is important to take a look at the Kansas City Art Institute, whose

alumni make up a significant portion of the local art world, and where I first met both Harbin

and Gallucci. In 2001 only 11.2% of students were minorities. More recently in 2016, the

number has grown to 32.5%((This does not factor student’s whose race/ethnicity is unknown.

For 2001, there is no data for 5.4% of the student body ( 29 students). And in 2016, there is

no data for 8.8% of the student body (56 students).)). Although KCAI has rapidly progressed

in building more equitable student demographics, this has not been the case over a longer

time frame. The consequences of these statistics over many years are an unhealthy lack of

diversity in Kansas City’s art scene.

Recently there was a comprehensive study of the U.S. art world done by the organization

BFAMFAPhD. With information from the 2012 U.S. Census. They looked at U.S. art schools

and working artists, and collected data for race and ethnicity. An excerpt from that study

shows while 63.2% of Americans identified as white, 80.8% of American art school

graduates identified as white. And this nearly 18% gap doesn’t take into account the

problematic structure of the census—for example people of middle eastern descent were

instructed to fill out the census as “white” because there wasn’t a separate category for them.

Receiving an arts education trains you to understand the logistics of the game and to market

yourself competitively for calls for proposals, grants, and other opportunities. You come out

of an arts education, even though sometimes awkwardly, walking the walk and talking the

talk. Cryptic art language and concepts are often unreadable to those who don’t hold a BFA,

which we’ve already seen isn’t a level playing field for all races and ethnicities. You could

even say that art world standards for “high quality, innovative art” are primarily established by

what goes on in art schools, so that many who have never attended will simply not fit the

profile. On top of all of this, it is clear you must have the capacity to move around a room and

network—social connections are a currency in our field, with art school giving you a built-in

head start. But what happens to those who don’t feel welcome even being in the room? To

those who don’t know anyone else in the room or don’t know the room exists? It is important

to keep in mind this underlying system of social-connections-as-capital and inaccessiblelanguage

and ideas-as-norm.

So, turning back to Front/Space we have to ask what the role of an alternative art space

should be when we understand that the art institutions providing education and exposure are

built to favor one racial group? In a field that mimics the racial inequity of our country, if an

institution does not actively make efforts to reach beyond its habitual audiences and

collaborators then it is accepting these injustices as a norm and continues to perpetuate

them. I believe there are questions that Front/Space, and all other white-led spaces, should

ask at every step of the way.

What could happen if the panel who decides the exhibitions at Front/Space is made up of not

only of past artists, but also of people who are actively engaged in equity issues and with the

communities which they do not yet have an established relationship?

Who is your intended audience? If left up to happenstance, the audience of a DIY art gallery

becomes the same insular community, which we know is skewed to prefer white folx.

What artists are showing in the space and benefitting your gallery?

How do you spread information about openings and events at Front/Space to new

audiences? If there are flyers or show cards, are you leaving any at locations where majority

people of color will encounter them? How can these invitations be genuinely delivered?

How does relying on word-of-mouth and social media algorithms that stay within

already established friend circles create an insular, white-majority community?

When the gallery is open, what small habits become exclusive? Who is allowed to go in the

back?

How is success being measured? Even with the reputation of a gallery that invites artists to

take risks, are those risks meaningful to those outside of our close-knit community, to those

who don’t speak an inaccessible art language?

Who is being asked to give feedback about Front/Space? How do we invite critical input from

our close friends and when do we purposefully ask those who are not close?

Image from Front/Space’s State of the Space event presentation courtesy of the gallery

As an arts community, we need to be better at addressing these issues. Over the course of

the night at the State of the Space, words like accessibility and audience came up, but we

never really stated the obvious—that Front/Space continually draws a uniform crowd. The

State of the Space was a perfect example of that, because, as far as I could tell, there were

very few people of color in the room. We need to be suspicious of our own activities when we

attract such an unvaried crowd without intending to do so. These discussions are not specific

to Front/Space. These issues need to be addressed at all levels and on all platforms—from

large art museums that have 84% ((Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Art Museum Staff

Demographic Survey)) white curators and leaders, to small DIY galleries that only reach

friends, to the host of this writing. Informality also needs to address the racial inequity

present in this publication.

As we move forward, our art world needs to ask for more and to hold each other to higher

standards—because we are capable of this kind of critique. We just need to work on shifting

some of it toward ourselves. To paraphrase the artist Simone Leigh at the 2016 National

Council for the Education for the Ceramic Arts, “making ceramic art for other ceramic artists

is like learning from your mother…Sympathy undermines your ability to be critical.” When

does our sympathy for our close-knit community undermine our ability to be critical?

Front/Space has been so valuable to me as a place that shows the potential of our

community and has been crucial in forming an understanding of the possibilities artists have

in our mid-sized Midwestern city. I am optimistic about Front/Space’s ability to be dynamic

and responsive. Their willingness to receive feedback from anyone who came to the State of

the Space is a great start; we just need to make sure the right people are in the room and

that they feel welcome to ask questions that will cause friction.