Light and Dark, Sight and Sound: Janet Cardiff- 40 Part Motet Meets The Photographs of Dave Heath

Image of Janet Cardiff’s 40 Part Motet. Image courtesy of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Photo Credit: Bob Greenspan

Walking through the Nelson-Atkin’s contemporary wing, you could hear the gently building

reverberation of Janet Cardiff’s 40-Part Motet. This sound piece and Multitude, Solitude:

Photographs of Dave Heath were advertised as a joint exhibition, but the synergy of both

shows became a happy accident. Motet is the stronger of the two, creating a joyful sound

experience which brightened Heath’s somber portraiture. His Multitude, Solitude are a collection

of mostly black and white photographs from 1931-2016, that dealt with themes of human

loneliness, “loss, uncertainty, pain, love and hope.” While Heath’s work awoke human despair,

leaving me raw, Cardiff’s work functioned as a salve, restoring hope that even in this broken,

violent world, we are still deeply interconnected.

Washington Square, New York City, 1958. by Dave Heath. Gelatin silver print, 12 1/2 x 8 3/8 inches. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri, Gift of the Hall Family Foundation, 2005.37.207.

The arrangement of both shows had Heath’s photography exhibition first. If one wanted to bolt

straight to Cardiff’s sound piece, as I did, you still needed to pass by his work first which sets up

an emotional tone for the viewer. Multitude, Solitude included photographs projected on the wall

and torn out pages from a book. Framed portraits, also too small, hung wall to wall, and digital flip

books of Heath’s work were presented at center. Undeniably beautiful, Heath’s street

photography captures the fleeting transition between emotions that can occur in public, but which

most rarely witness; capturing a secret smile, a glimpse of joy or a moment of loneliness.

However, the weakest aspect of this show was its set up. Torn-out book pages were framed

in such a way they cut off portions of several images and the digital archive of Heath’s

photography looked like an afterthought. The curator crowded the room with similar imagery

when strong editing could have made the very same points with more elegance. This

abundance of repetition made it difficult to decipher the overall strength of his work, and was

more likely a disservice to his keen photographic eye. Selecting a few of Heath’s strongest

works from each decade would have been a simpler approach. Although it is unclear

whether or not the two exhibitions were meant to be viewed in tandem, giving more

consideration to an intended interaction between Heath and Cardiff’s work would have

elevated the creative synergy from both artists.

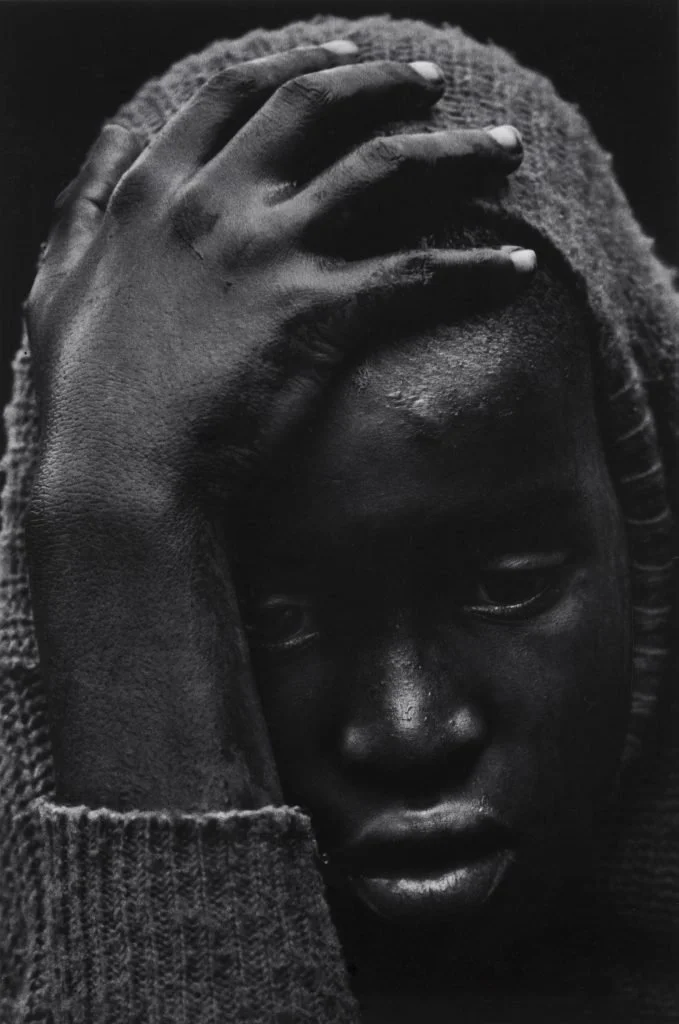

The audience become voyeurs with Multitude, Solitude, witnessing archived loneliness in the

faces of passers-by. With each wrinkled brow or teary stare, we get a glimpse of humanity’s daily

suffering, how one can feel isolated in a crowd, or even the task of getting through the day. These

images tear into that part of our hearts where walls are built, the sensitive core that makes us

turn off the news or avoid eye contact. Photography gets painfully close to the truth, illuminating

how frequently we gloss over moments of pain with desperate optimism.

Image from Heath’s Multitude, Solitude. Image courtesy of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Outside the 40 Part Motet, a wall of notecards provided museum-goers an opportunity to record

their thoughts right after any epiphanous moment. Overarching themes of connectivity and

spirituality came through, despite the variety of backgrounds and beliefs. Though I am skeptical

Nelson curators went into enough depth examining the conceptual interaction between the two

exhibits, these notecard reflections epitomized the Multitude, Solitude of Heath’s work. “Motet”

transcends human understanding of this world, of art, of music, even of religion. With Heath’s

work, one begins to think one understands what it means to be human, and that much of the time

it can be unpleasant. Cardiff’s work, on the other hand, takes us out of our deep-seated cynicism

and competitive mentality without washing away our individuality or community.

My best friend and I entered the Motet space together, then quickly split up, allowing us to have

separate experiences not influenced by our friendship. We walked in near the end of the recording,

but it played on a loop every fourteen minutes or so. 40-part Motet is a collection of inward-facing

speakers arranged in an oval, where visitors can sit on benches, stand, or walk around the interior.

The speakers are arranged in eight groupings, for the eight different choirs recorded. Every

speaker has its own a cappella voice from England’s Salisbury Cathedral Choir, singing in Latin.

Surrounded by these speakers, the audience became a silent hive. It was refreshing in that the

reverence for the music went beyond modern museum etiquette. No one had their phones out for

photography or recording, an anomaly. It was as if they were in a place of worship. Some stood,

meditating before one speaker, some walked methodically in thought around the room, some sat

on benches, some even sat cross legged on the carpet, with closed eyes. I couldn’t find words to

describe this energy yet, but it had something to do with peace, with connectivity, and it was

transforming the space.

Image of Janet Cardiff’s 40 Part Motet.

Photo Credit: Maddie Murphy.

The combination of 40 voices struck me immediately, giving me goosebumps as the song

swelled from a soft hum to a booming wave of vibration and sound. I stood at center for a

moment, already tearing up, and closed my eyes to feel the energy of the room. Due to its

circular arrangement, Cardiff’s work enveloped the audience, as if we had entered inside the

music itself.

It was deeply important that I absorb every vibration. Forty individual voices with unique

inflections blended into sharp, clear sopranos, deep basses and baritones, and sweet tenors.

I imagined the speakers were people, not technology and they were singing directly to both

me and a higher power. I became the most emotional when the intensity increased and the

harmonies hit full blast. I forgot where I was and who I was with, the beauty of the work

stirred a sad, aching joy of happy tears. My fellow listeners and I became vulnerable,

perhaps experiencing contemporary art of this genre for the first time. Looking around the

room, people of all ages and ethnicities were present, many with the same misty-eyes I had.

Just as the multitude of voices combined into one voice, never losing the variety of tones and

voice types, we became one, never losing what made us uniquely ourselves.

Image of Janet Cardiff’s 40 Part Motet. Image courtesy of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Photo Credit: Bob Greenspan.

I recognized the potential for universality, especially after reading audience reactions, which

ranged from “God spoke to everyone here,” to “Namaste,” to a nearly blank card with a tiny

word, “Wow.,” written at the bottom corner. Performed in a language few know, the audience

relied solely on emotional energy to comprehend the song.

I spotted one girl, likely near my own age, sitting cross legged on the floor, eyes closed and

weeping. I sensed she was deeply spiritual like I am. But I let it go, understanding this was

one of those fleeting moments similar to Heath’s work in the next room.

At the intermission, the recorded singers began speaking to one another, a different sort of

bubbling chorus. We could hear a young choir member saying she had to use the bathroom.

The other members discussed the weather, coughed, laughed, and warmed up their voices.

It was these sort of breaks that changed the tone of the piece and the audience was

pleasantly startled by this sudden inclusion of humanity. It also broke the tension in our

atmosphere too; people began speaking, our own voices united with the chorus. Based on

Cardiff’s interviews, I don’t know that she intended this inclusion as an opportunity for the

audience to relax, though it functions as such. Cardiff wanted to highlight the way run-of-themill

human speaking voices can metamorphose into an angelic choir in a single breath.

During my research it became apparent how much this musical sculpture could transform its

surroundings based on the work displayed. In The Art Gallery of Ontario, Motet was situated

near a collection of spotlit abstract sculptures. At the Nelson, Cardiff’s piece stood alone

visually, but the sound carried into different exhibits. Placing Motet on its own prevented

visual distraction, but sound can rarely be contained between dividing walls. While other

works could not disrupt Motet, Motet radiated out into surrounding galleries. I’m not certain

Heath’s Multitude, Solitude would stay in memory when Motet washed over the room, but

when I forced myself to see the photo exhibit, I couldn’t get the music out of my mind.

Though Cardiff’s Motet had traveled across many continents, it remained a remarkably

universal, immersive experience. Reactions to the work touched on it’s spiritual nature,

calling it “a choir of angels in heaven” or “a connection with God.” Other notes commented

on how it united the room, even the world, reminding us how our different voices come

together as one humanity. Most artists struggle to communicate ideas or emotions visually or

through sound; Cardiff is a master of both. What makes 40-Part Motet so revolutionary is that

it doesn’t require us to decipher by listening or by seeing, but rather requires us only to feel.

Multitude, Solitude also made us feel the power in its honesty and leave us to ask, what is

the solution to suffering? Motet was cathartic, fourteen minutes of healing I wished could be

a daily practice. Works like these offer a way to recover enough to find our own answers.

Janet Cardiff’s 40-Part Motet and Multitude, Solitude: Photographs of Dave

Heath were temporary exhibits at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, which ran from

November 19, 2016 to March 19th 2017.